From skepticism (mostly in newsrooms) to irrational exuberance (the nerds in the building), the emotions ran the gamut. Since then, the shocking advances of generative AI have continued to force the industry to assess in real time its stance on AI. As Brian Morrissey, one of the industry’s most astute observers, wrote in his newsletter The Rebooting: "In the best scenario, we will become super-empowered, and even more barriers to media creation will be eliminated. In the worst case, we’ll have bots writing for bots, monetized by bots."

Let’s be honest: Resistance to AI is probably futile, especially for a sector that has been undergoing decades of disruption due to three unstoppable forces:

the platforms that have taken command of advertising

the social apps and streamers that have hooked younger audiences

and the corporate owners who are cutting costs in an attempt to stay one step ahead of terminal decline.

To wit: After threatening legal action against OpenAI and blocking data-hungry scraping bots, some of the largest publishers – including legacy brands like Reuters and Hearst and digital natives like Vox – signed multimillion-dollar deals in 2024 to share content with the ChatGPT maker.

The industry is divided between Dealmakers and Resisters in the new era of AI tech giants

And while a handful of “resisters,” including The New York Times, remain in fight mode, suing OpenAI for copyright infringement, few hold out hope that news companies will slow the march of the Big Tech firms who have a surplus of cash, lawyers and lobbyists to pursue their “next new thing.” (It should not escape notice that major grant funders of AI innovation in news are Google and Microsoft.)

Maybe AI will save us, some media members now speculate.

In September, thousands of news industry professionals streamed into a downtown Atlanta hotel for the Online News Association’s annual conference, eager to glean “insights and ideas to build the next iteration of excellent, innovative media.” And, no surprise, AI was a dominant theme on the agenda.

Nearly every hour over three days featured a session on AI’s calibrated but inexorable adoption by the industry. Topics ranged from integrating AI into newsroom workflows to ethical uses of Gen AI’s creative powers (think producing AI-generated audio reads of news articles).

There was an audible gasp during a standing-room-only session when a featured speaker showcased how AI can already be used to ingest long-form videos and in just minutes generate a collection of quick clips formatted and optimized for social media distribution and algorithms.

Clearly, the industry's stance has evolved from cautious skepticism to cautious embrace. And there is growing consensus that trustworthy and specially trained AI can both assist and amplify news in effective and acceptable ways.

Zooming out, we see three AI adoption trends emerging in the industry in 2025:

Foundation Building: Where AI’s value is clear and proven and the risk it poses is low.

Calculated Innovation: Where AI's potential seems high, but there's more risk. Experimentation, fine-tuning and beta testing are required.

Disruptive Game-Changing: Where AI advances hint at dramatically new possibilities – e.g., Google NotebookLM-generated podcasts based on news articles. But the risk is clear and far more consequential: Are we willing to make news experiences more synthetic and less human?

The news industry's fascination with AI predates the launch of ChatGPT. Since 2014, the Associated Press has used AI to generate earnings reports for its business feed. In 2016, The Washington Post launched Heliograph, an AI tool that converts sports and election data into brief summaries.

These early AI initiatives required significant investment and complex development involving data science, machine learning, and natural language processing.

Generative AI, however, has changed the landscape, making AI more accessible by allowing newsrooms to tap into large language models – like OpenAI’s API — through affordable subscription models.

And there is a growing consensus about where AI can improve newsroom productivity and creativity today – as long as there is a human in the loop. (For more fine-grained details, see the Associated Press survey results in this 2024 report.) The “acceptable AI” features – or “use cases” in the parlance of product development – fall into three areas:

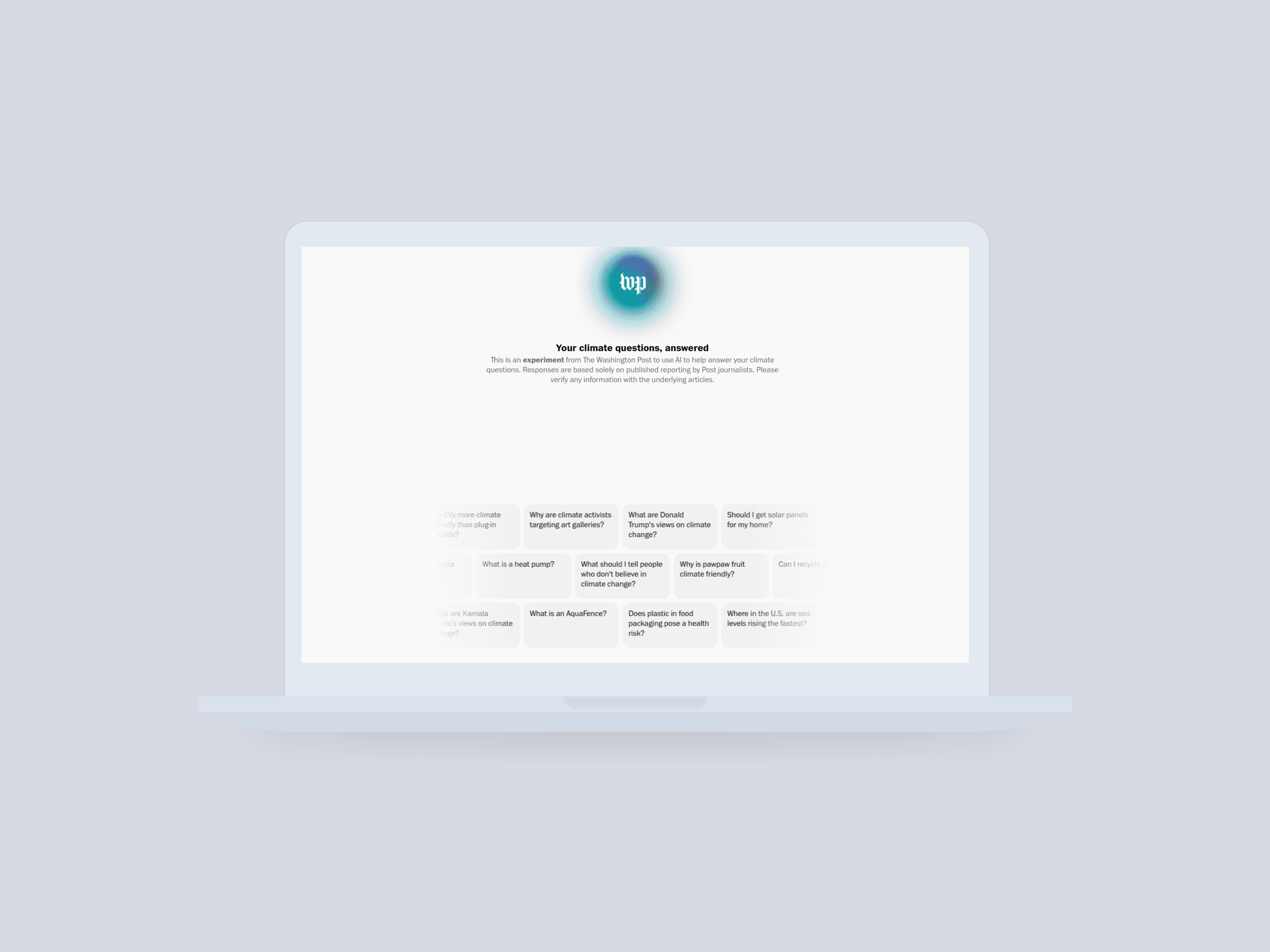

The Washington Post this year launched a “Climate Answers” chatbot trained on more than two decades of the Post’s environmental coverage. “We are always looking for innovative ways to present our journalism,” the Post explained to readers “The rise of chat interfaces powered by generative AI got us thinking: How could we offer an experience that leaned into the expertise and high-quality reporting produced by The Post?”

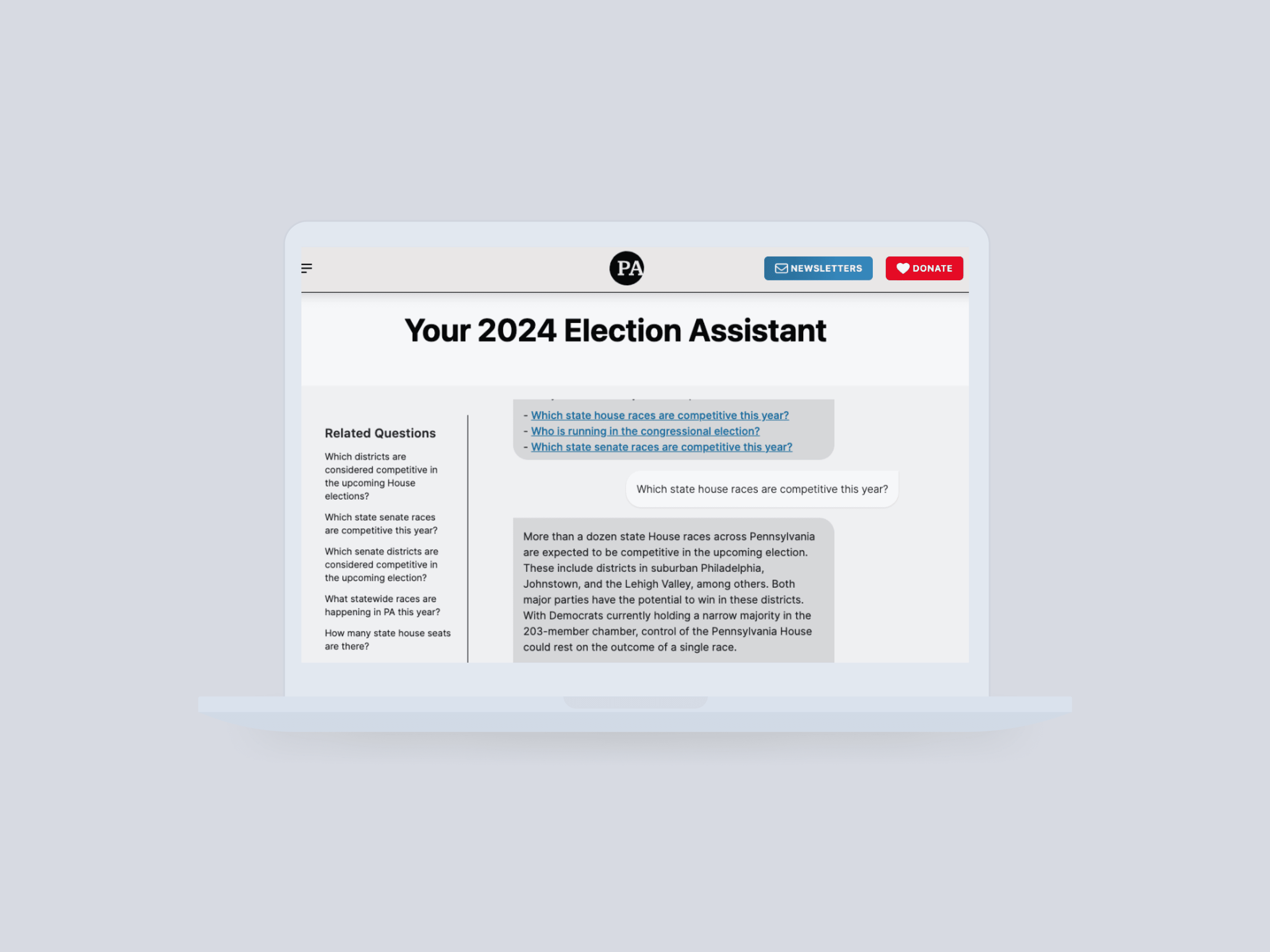

Spotlight PA, a non-profit news operation focused on investigative and public-service reporting for Pennsylvania, introduced an Election Assistant chatbot in the weeks leading up to the November election. “Every year, Spotlight PA receives countless questions about the election process, but our limited staff and resources make it hard to answer every inquiry individually,” Spotlight readers were told. “The Election Assistant will help thousands of readers find clarity and facts on a subject that has become a lightning rod for confusion and partisanship.” An added benefit of the bot: with a click, it can interact in Spanish.

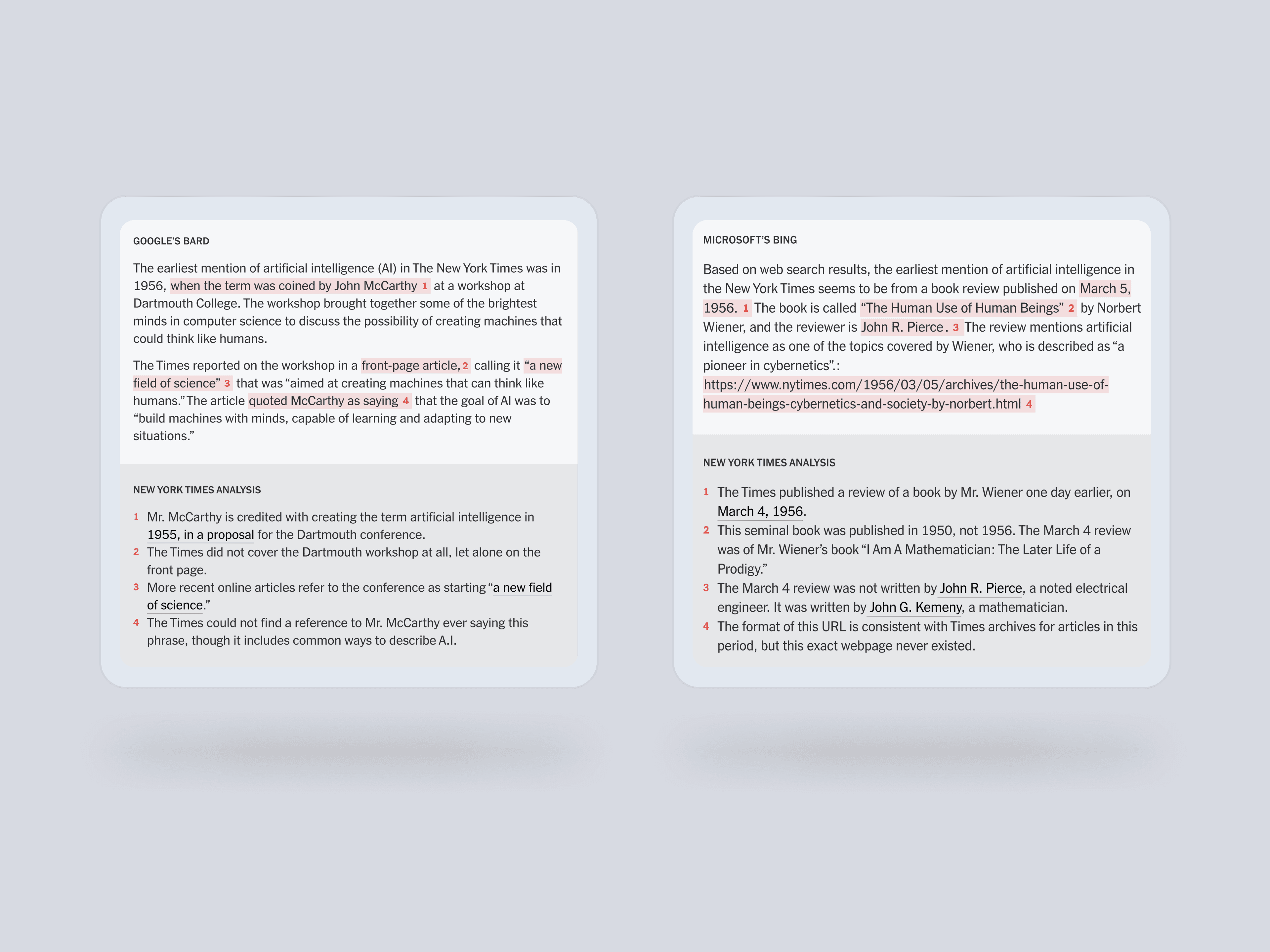

The fear of AI “hallucinations” – when a system generates inaccurate or misleading content – remains the biggest “blocker” for many newsrooms eyeing chatbots. While extensive editorial testing and fine-tuning can reduce the risk of AI fibs, these approaches are time-consuming and not guaranteed to fully eliminate errors. This is where a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) model and vector database come into play.

With RAG, AI systems don't rely solely on their internal models to generate content. Instead, they retrieve relevant, factual information from a trusted, pre-curated database before generating an output. For publishers, that database would be made up of hundreds of relevant articles. By grounding responses in verified data, the RAG approach helps to ensure that AI chatbots are more likely to produce accurate, reliable content.

While work to improve the editorial reliability of chatbots continues, we expect to see them become more prevalent in the next year. The reason: They offer a glimpse of what the next-generation news experience will become – more interactive, more personalized, and more deeply engaging. A news chatbot allows a user to have a conversation with a credible, authoritative “expert” for news, weather, sports, events, politics, entertainment, and more. Indeed, a chatbot can be a step up from the clunky site search experience that has long plagued news sites.

As for publishers, the business value is every bit as compelling. Early signs indicate news bots can increase time on site, drive more page views per visit, and provide a rich source of data insights about what topics are driving audience conversations. And as a new revenue vehicle, chatbots can deliver targeted ads or be offered as a premium subscription benefit.

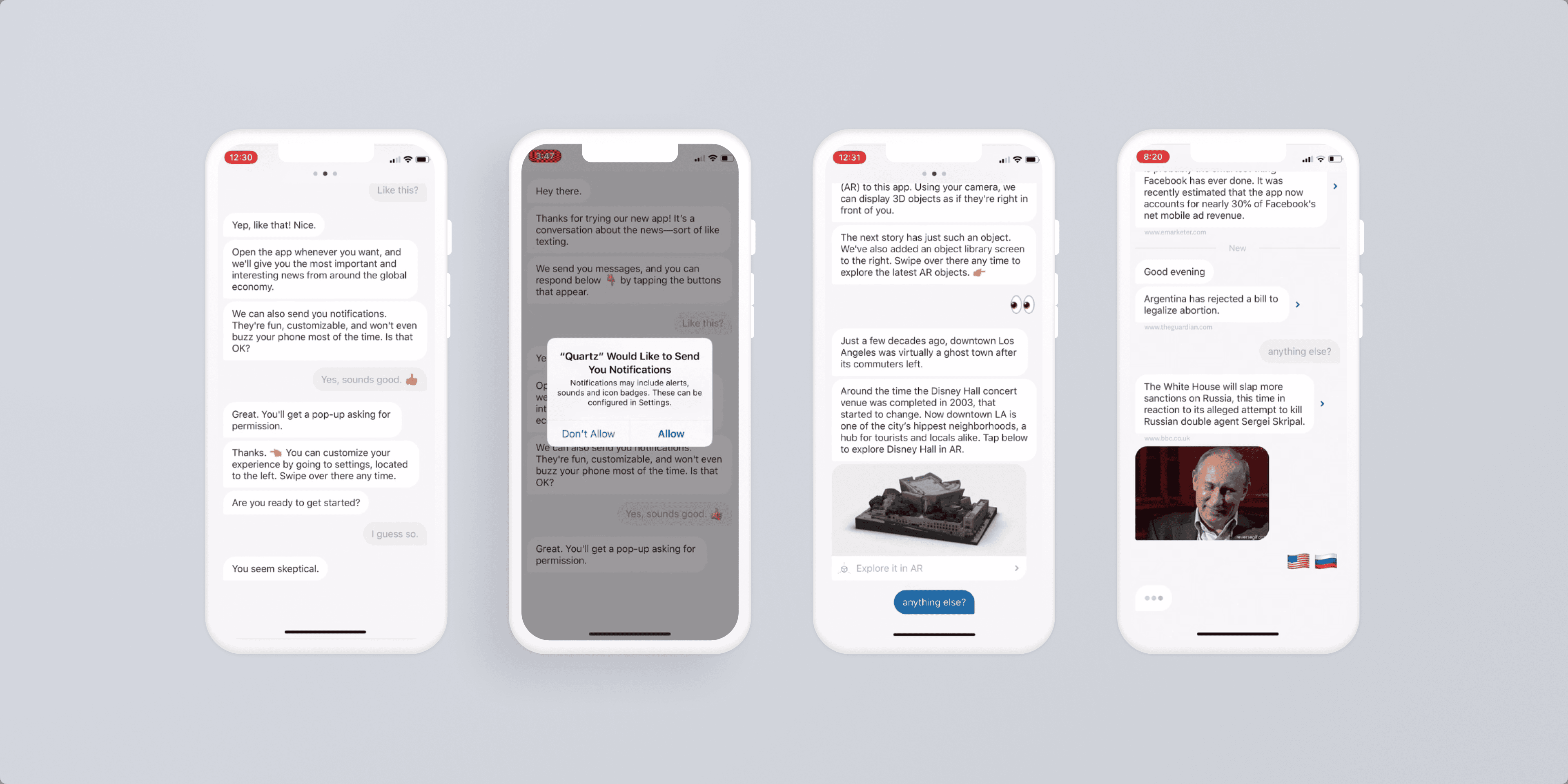

The key question: Will the Gen AI-powered version of a news chatbot succeed where earlier versions – most notably Quartz Brief, which was shut down after three years of generating favorable buzz but few downloads – failed? A new generation of audiences will make that decision.

There are few more compelling examples of how AI could radically change the way news and media are experienced than NBC’s AI version of Al Michaels. The legendary broadcaster’s AI-generated voice was used to narrate hundreds of variations of daily streaming recaps during the 2024 Summer Olympics.

“When I was approached about this, I was skeptical but obviously curious,” the 79-year-old Michaels told The New York Times. “Then I saw a demonstration detailing what they had in mind. I said, ‘I’m in.’”

Al Michaels, NBC Sports Anchor

What is human and what is synthetic will continue to be blurred as disrupters redraw the lines with every new demonstration of AI’s capability to mimic humans.

A broadcaster in Poland this year took NBC’s experiment one step further: State-owned Off Radio Krakow fired its on-air announcers and replaced them with AI-generated hosts with distinct Gen Z personalities. Station executives contended it was experiment aimed at attracting a younger audience. But the station’s flirtation with AI was brief. After public outcry, the experiment was suspended.

And then there is Google NotebookLM, a virtual research assistant that some are declaring a game-changer for journalists. Upload documents and information sources – PDFs, notes, videos, or websites – and NotebookLM will generate summaries and answer questions about what’s in the material through a chat interface.

Impressive enough. But the envelope-pushing feature that went viral is NotebookLM’s ability to create a “talk show” podcast – with two very human-sounding synthetic hosts – based on the content you’ve uploaded. While still an experiment – one that can create hallucinations – Google does not dispute the significance of the audio feature.

“The magic of the tool is that people get to listen to something that they ordinarily would not be able to just find on YouTube or an existing podcast,” says Raiza Martin, who leads the NotebookLM team inside of Google Labs.

How far could AI cloning go? There are three disruptive game-changing scenarios we believe could emerge in 2025.

Opinion writers and network anchors – especially in this age of Thought Leaders and Influencers – are the “stars” of news. With their distinct expertise (e.g., economist-turned-New York Times columnist Paul Krugman) or “hot take POV” (e.g., MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow), these media movers and shakers have attracted followers who buy their books and flock to their on-stage appearances.

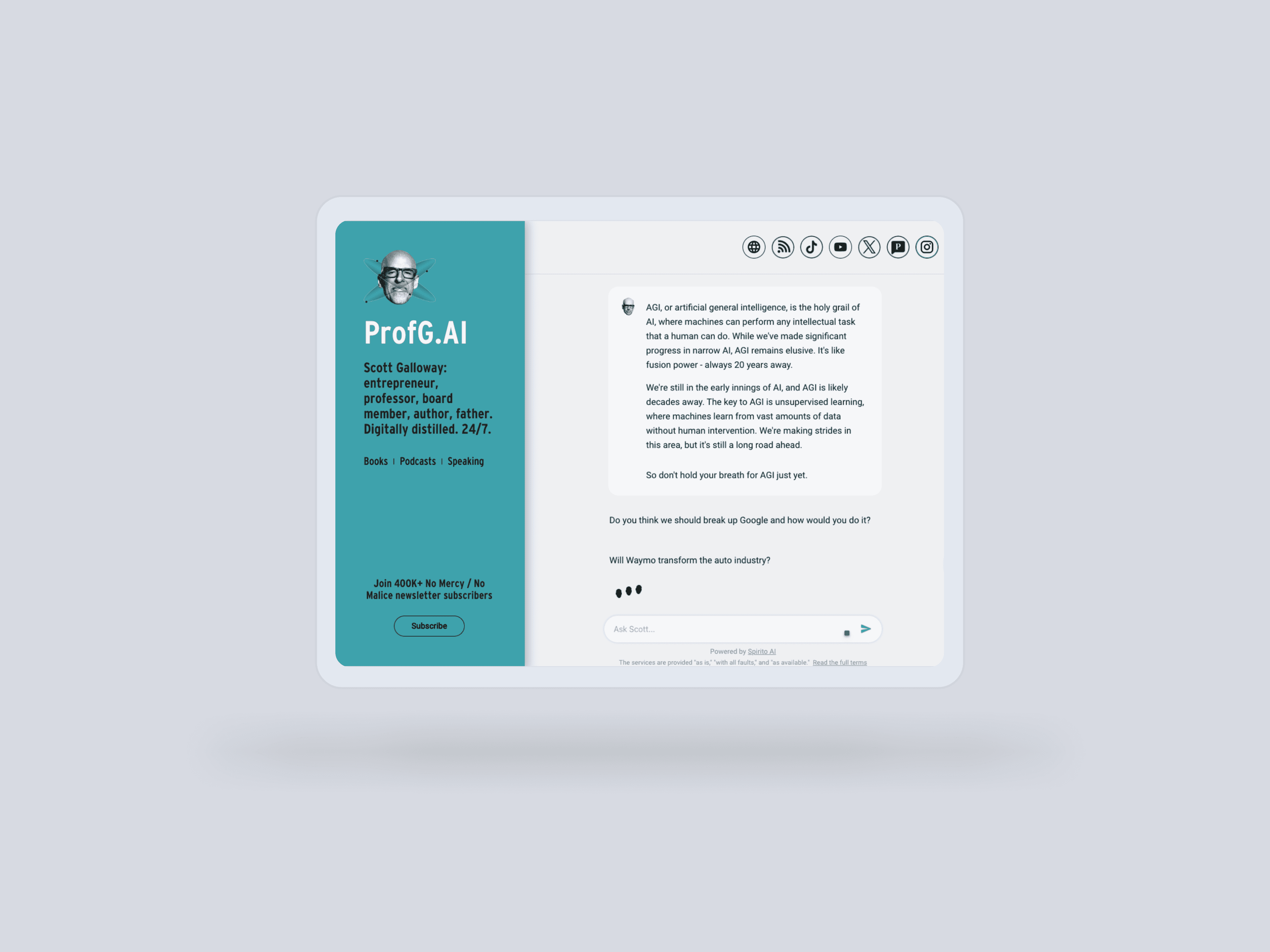

By training large language models on their published content – columns, video and audio transcripts, and speeches – it is now possible to create digital twins of news personalities: chatbots that can hold conversations like them, as well as audio and video avatars that look and sound like them.

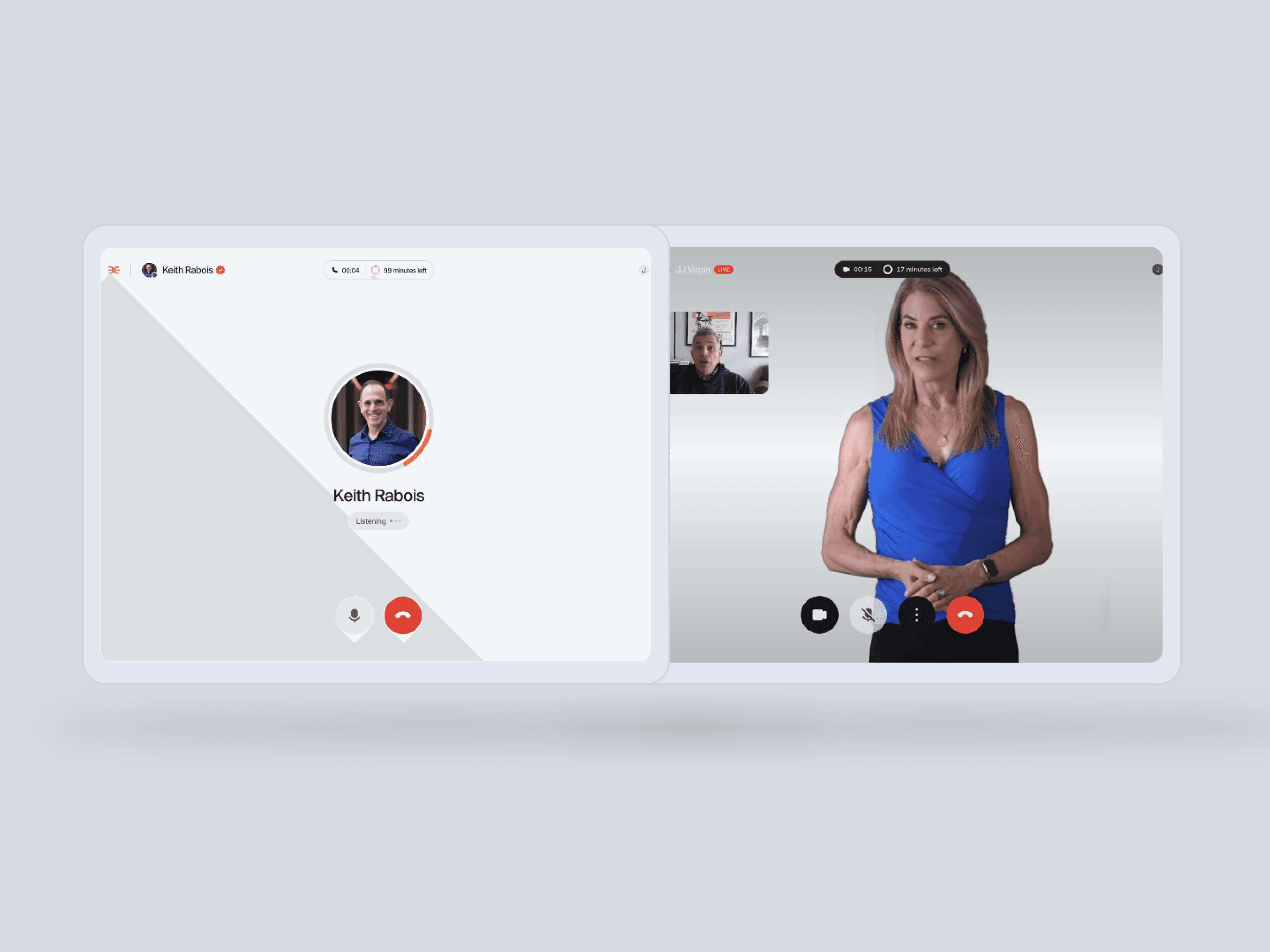

Delphi is a venture-backed startup that has launched with a slate of approved “clones” representing big name authors, entrepreneurs, music stars, and fitness gurus. You can text with them, call them and jump on a video chat with them 24/7 – for a monthly membership fee.

How lifelike are they? Slightly. And do they say things that are “off script”? It’s unclear. So establishment media companies are going to be very leery about digital twins. But some media personalities who operate independently are already taking the leap – including author, podcaster, and cable news regular Scott Galloway, whose ProfG.AI responds to questions with the blustery confidence of its provocateur namesake.

As avatars become more prevalent – and more eerily human-like – the potential benefits of synthetic stars, created with permission and a monetization model, may prove too attractive to ignore.

When Amazon launched the Echo with the Alexa voice assistant in 2014, even the company’s founder Jeff Bezos was skeptical of the device’s success. "No customer was asking for Echo. This was definitely us wandering," he told shareholders. Fast forward a decade: More than 500 million Echos have been sold, and asking Alexa for the latest news headlines is one of the most popular daily interactions.

Alexa seems quaint compared to ChatGPT’s advanced voice mode, which demonstrates just how far LLM-powered automatic speech recognition and synthesized voice generation has advanced.

Human-like conversational voice will transform more than the call center customer service experience. Imagine a scenario where instead of reading articles, you engage in natural language conversations about current events with an AI voice app on the homepage of your favorite news site. Drawing from a vast database of news articles and historical context, the voice bot could go beyond delivering the “five things you missed” headlines and answer follow-up questions, provide deeper historical background on complex issues, and even offer multiple perspectives on contentious topics. It would be like having a knowledgeable journalist on call 24/7, ready to explain and contextualize the news for each individual user. And the voice bot could mimic your favorite journalist’s voice – switching to Spanish with a verbal prompt.

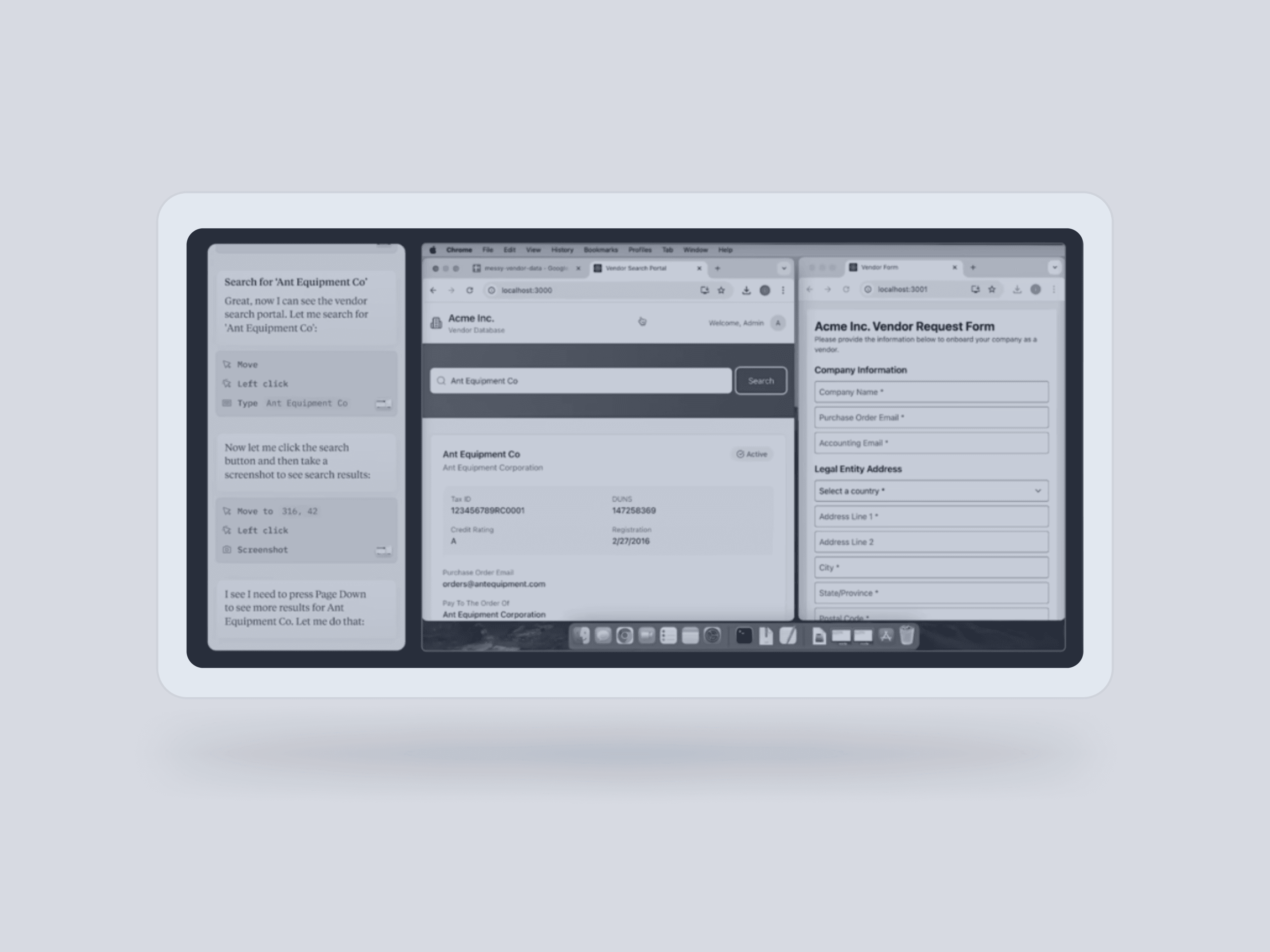

As 2024 comes to a close, the attention has shifted to another AI breakthrough: autonomous agents that can carry out increasingly complex tasks based on a user’s request. The race to create the “killer app” version of AI agents involves well-funded startups and all the major AI players, including Anthropic, which in October announced it’s giving its ChatGPT rival Claude what it calls “computer use” capabilities.

Though the beta version of Anthropic’s “computer use” agent is error prone, it provides a glimpse of what’s next: a computer bot that can open your browser, scan the Web, log in to applications and buy a product all on your behalf.

Claude's 'computer use' can open your browser, scan the Web, log in and buy products on your behalf

For news and media companies, the AI agent future could bring a new form of interaction, where a reader finishes an article about an exciting travel destination or a trendy local restaurant and, through an integrated conversational AI or voice assistant, can immediately have the agent book a flight, hotel, or dinner reservation.

In the emerging new world of AI agents, local newspapers, in a bid to recapture their once-central role in the lives of readers, could serve as both news providers and local concierges, offering personalized content alongside services like sports event bookings or restaurant reservations – and earning transaction fees along the way.

That’s the rosy future. Ezra Eeman, one of the industry’s most astute technology observers, warns that AI agents could also bring new challenges. “If today's 'dumb' bots already overwhelm news sites, imagine what smart ones could do,” he warned. “First tests show (Claude’s) Computer Use solving CAPTCHAs and beating Wordle in three guesses.”

As AI becomes more deeply woven into journalism, media leaders face a difficult and delicate balancing act. The potential benefits are clear: increased newsroom efficiency, new reporting capabilities, more personalized user experiences, and new revenue opportunities. But these must be weighed against the risks: the potential for mistakes and bias by AI systems, the diminishment of human judgment in editorial decisions, and the challenge of maintaining reader trust in an increasingly AI-influenced news landscape.

The key for news leaders will be to harness AI's capabilities while doubling down on uniquely human journalistic skills – critical thinking, ethical judgment, and the ability to build relationships with communities and tell compelling stories.

As we stand at this technological crossroads, one thing is clear: The future of journalism will be shaped by those who can successfully navigate the integration of AI while staying true to the core principles of the fourth estate. The challenge isn't just technological – it's existential.